Knowledge of x86 is important in security fields like malware analysis, vulnerability research and exploit development. The only prerequisite is to know the basics of C or C based languages like Java.

Bits, bytes, words, double words

The data “types” in 32 bits assembly are bits, bytes, words, and dwords. The smallest of them is the bit, which can be either 0 or 1. A byte is eight bits put together and can be between 0 and 255 A word is two bytes put together, or sixteen bits, and can have a maximum value of 65535. A dword is two words (d in dword stands for double), four bytes or 32 bits. The maximum value is 4294967295.

Registers

A register is a small storage space available as part of the CPU. This also implies that registers are typically addressed by other mechanisms than main memory and are much faster to access. Registers are used to store values for future usage by the CPU and they can be divided into the following classes.

General purpose registers

Used by the CPU during execution. There are eight of them and the original idea of Intel engineers was that most of these registers should be used for certain tasks (their names hint the type of task intended). But during the years and the development of Intel architecture each and every one of these can be used as general purpose register. That is however not recommended. EBP and ESP should be avoided as much as possible, as using them without saving and restoring their original values means the functions stack frame will be messed up and the program will crash.

EAX) Extended Accumulator Register EBX) Extended Base Register ECD) Extended Counter Register EDX) Extended Data Register ESI) Extended Source Index EDI) Extended Destination Index EBP) Extended Base Pointer ESP) Extended Stack Pointer

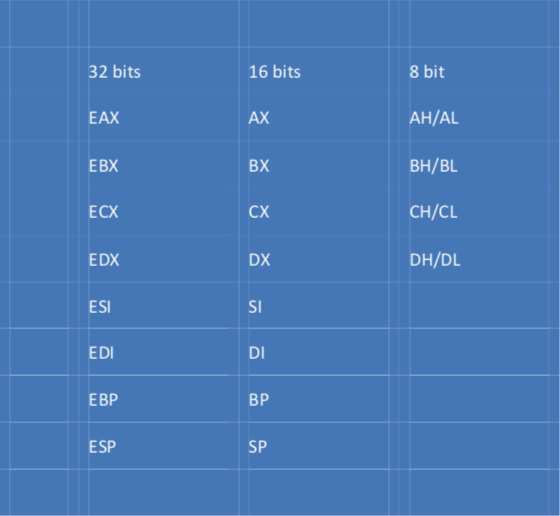

All the general purpose registers are 32-bit size in Intel’s IA-32 architecture but depending on their origin and intended purpose, a subset of some of them can be referenced in assembly. Below is the complete list.

AX to SP are the 16 bit registers used to reference the 16 least significant bits in their equivalent 32 bit registers. The eight bit registers reference the higher and lower eight bits of the 16 bit registers.

Segment registers

Segment registers are used to make segmental distinctions in the binary. We will approach segments later but in short, the hexadecimal value 0x90 can either represent an instruction or a data value. The CPU knows which one thanks to segment registers.

Status flag registers

Flags are tiny bit values that are either set (1) or not set (0). Each flag represent a status. For example, if the “signed” flag is set, the value of FF will represent a -1 in decimal notation instead of 255. Flags are all stored in special flag register, were many one bit flags are stored at once. The flags are set whenever an operation resulted in certain state or output. The flags we are most interested in for now are: Z – zero flag, set when the result of the last operation is zero S – signed flag, set to determine if values should be intercepted as signed or unsigned O – overflow flag, set when the result of the last operation switches the most significant bit from either F to 0 or 0 to F. C – carry flag, set when the result of the last operation changes the most significant bit

EIP - Extended Instruction Pointer

The instruction pointer has the same function in a CPU as the needle had in those old gramophones your grandpa used to have. It points to the next instruction to be executed.

Segments & offsets

Every program consists of several different segments. Four segments that each program must have are .text, .data, .stack and .heap. The program code is put in .text and global data is stored in .data. The stack is where, among many things, local variable and function arguments, are stored and the heap is an extendable memory segment that programs can use whenever they need more memory space.

The stack

The stack is the part of memory where a program stores local variables and function arguments (among many things) for later use. It is organized as a “Last In First Out” data structure. When something is added to the stack, it is added on top of it and when something is removed, it is removed from the top. Another very important feature about the stack is that it grows backwards, from the highest memory address to the lowest, more about that in a moment. Two registers that are customized to work closely with the stack are the ESP and EBP. The ESP is the stack pointer and always points to the top of the stack. When something is added to the stack, the stack grows. This means the ESP needs to be corrected to point to the new “top” of the stack, which is done by decrementing ESP. Again, this is because the stack grows backwards, from highest address to lowest.

Stack frames

The EBP is the base pointer but what does base mean? Well, every process has at least one thread, and every thread has its own stack. And within the stack of every thread, each function has its own stack frame. The base is the beginning of a stack frame. The main function in every program has its stack, when it calls a function the called function creates its own stack frame which is marked out by the EBP that points to the beginning of the functions stack frame and the ESP that points to the top of the stack. More about this subject later.

The Heap

The heap is memory space that can be allocated by a process when it needs more memory. Each process has one heap and it is shared among the different threads. All the threads share the same heap. The heap is a Linked-List data structure, which means each item only knows the position of the immediate items before and after it. When the process does not need the memory anymore, it is custom to “free” the allocated heap. This is done by de-referencing the no longer required portion and allowing other processes to use it.

Instructions

Intel instructions vary in size from one to fourteen bytes. The opcode (short for operation code) is mandatory for them all and can be combined with other optional or mandatory bytes to create advanced instructions. This is a vast topic and further reading is done at the links below for those who want. If not, the disassembler will do the job for you, but it can be good to know why opcode 83 sometimes is disassembled as an add and other times as an and instruction when you look in your disassembler. Below links will explain that indirectly. http://www.swansontec.com/sintel.html http://ref.x86asm.net/coder32.html Most instructions have two operators (like add eax, ebx), but some have one (not eax) or even three (“imul eax, edx, 64”). Instructions that contain something with “dword ptr [eax]” reference the double word (4 byte) value at memory offset [XXX]. Note that the bytes are saved in reverse order in the memory as Intel uses Little Endian representation. That means the most significant bit of every byte is the most left bit.

Arithmetic operations - ADD , SUB, MUL, IMUL, DIV, IDIV…

ADD, syntax: add dest, src Destination and source can be either a register like eax, a memory reference [esp] (anything surrounded by square brackets is an address reference). The source can also be an immediate number. Noteworthy is that both destination and source cannot be a memory reference at the same time. Both can however be registers. add eax, ebx ; both dest and src are registers add [esp], eax ; dest is a memory reference to the top of the stack, source is the eax register add eax, [esp] ; like the previous example but with the roles reversed add eax, 4 ; source is an immediate value

The sub instruction works exactly as the add instruction. SUB, syntax: sub dest, src

The division and multiplication instructions are a little different, let’s go through division first. DIV/IDIV, syntax: div divisor

The dividend is always eax and that is also were the result of the operation is stored. The rest value is stored in edx.

mov eax, 65 ; move the dividend into eax

mov ecx, 4 ; move the divisor into ecx

div ecx ; divide eax by ecx, this will result in eax containing 16 and edx containing the rest, which is 1

IDIV is the same as DIV but signed division.

MUL/IMUL, syntax: mul value mul dest, value, value mul dest, value

mul/imul (unsigned/signed) multiply either eax with a value, or they multiply two values and put them into a destination register or they multiply a register with a value.

Bitwise operations – AND, OR, XOR, NOT

AND, syntax: add dest, src OR, syntax: or dest, src XOR, syntax: xor dest, src NOT, syntax: not eax

Bitwise operations are what their name suggests. Two pieces of data are being compared bit by bit and depending on the operation, the outcome is either a 0 or a 1. Consider below two values:

value 1: 10011011 value 2: 11001001 output: ????????

If the operation is AND the output would be 10001001 since only the 1st, 5th and 8th bits in both value 1 and 2 are set. That is what AND means, it checks for equally positioned bits that are both set. If the operation would be OR, it would check for any set bites and as long as a bit is set in either value 1 or value 2, it would set the equivalent bit in the output. Hence the result of an OR would be 11011011. The XOR is like the OR but with one very important distinction. It will not set bits in the output were both bits are set, instead it will only set bits that are exclusively set in either value 1 but not 2, or the other way around. The above example would give the following output: 01010010. The way XOR works brings an interesting feature, any value XOR:ed with itself will become 0. Many compilers are making use of this feature of the XOR operation by XOR:ing a register with itself instead of moving the value 0 into it, as the XOR operation will go faster. The NOT operation is different to the other bitwise operations as it only takes one value and inverses every bit. For example the value 11011110 would become 00100001 when NOT’d.

Branching – JMP, JE, JLE, JNZ, JZ, JBE, JGE…

JMP/JE/JLE…etc syntax: jmp address

In assembly, branching is made through the use of jumps and flags. A jump is just an instruction that under certain circumstances will point the instruction pointer (EIP) to another portion of the code (much like the “goto” keyword in C). Flags are, as mentioned previously, tiny one bit values that can be set (1) or not set (0). Most instructions set one or more flags. Let’s revisit some of the instructions we already looked at and see which flags they set ADD can set all of the Z, S, O, C flags (and some more that are of no interest to us right now) according to the result. Same is true for the SUB instruction. The AND instruction however always clears the O and C flags, but sets Z and S flags according to the result. Depending on which flags are set, a jump will either happen or not. As you see, there are always only two options in assembly branches and if you think about it, this is also true in all the more complex type of branches that higher level languages offer. A switch statement in C for example will always perform or not perform a case, then move on to the next case and once again decide whether to perform or not perform that case. Two notes! First of all, most of the time you will see an instruction called CMP (which stands for compare) being used before a jump. CMP is the ideal pre-branch instruction as it can set all the status flags and is really fast. The syntax for CMP is: cmp dest, src This does not mean the other instructions cannot be used before a jump, for example XOR occurs frequently but the most common is the CMP instruction. The other important note is about the jump instructions. There are a lot of jump instructions and nobody can memorize them all. Often there are several jumps that look very much alike. For example, JLE stands for “Jump Less or Equal”. In C this would be: if (x <= y) { do this } At the same time, JBE stands for “Jump Below or Equal”. Which in C would be: if(x<=y) {dothis} So why these different jumps that looks exactly the same in C, one wonders? The answer is “due to signed and unsigned comparisons”. JLE is used to check the flags after a comparison between signed variables and JBE for unsigned comparisons. This was just an example, unless you memorize them all, you always need to read in the Intel Developer’s Guide to see which flags a jump checks for.

Data moving – MOV, MOVS, MOVSB, MOVSW, MOVZX, MOVSX, LEA…

MOV, syntax: mov dest, src MOVSB, syntax: movzx dest, src MOVZX, syntax: movzx dest, src

MOV moves data from source into destination. Both source and destination can be register, or one of them register and the other one a memory reference. Both cannot be a memory reference however. The mov instructions come in many flavours, just like the jump instructions, and partly for the same reason. MOVS/MOVSB/MOVSW/MOVSD for example copy a byte, word or dword from source to destination. The mov instructions that have an X in their name are used for variable extension. In C it would for example be like a typecast from char to integer, like this

char a = ‘h’; int b; b = (int)a;

The instructions work like this

MOVSX) DEST <– Signextend[SRC] MOVZX) DEST <– Zeroextend[SRC]

Where signed means the extension bits will hold the value of one. Another instruction that can be used for data moving is the LEA instruction. LEA stands for “Load Effective Address” and the syntax looks like this:

lea eax, dword ptr[ecx+edx] ; This will store ecx+edx in eax

Loops – LOOP, REP…

Although one can create neat loops using jumps, Intel’s x86 assembly also provides instructions specifically tailored to create iterating sequences of code. Like many of the other instructions we looked at, they come with many flavours depending of the size and sign of the variables they work with. For simplicity reasons, I will only show the easiest cases, LOOP first:

mov ecx, 5 ; remember ecx stands for extended counter register

_proc:

dec ecx ; decrements ecx

loop _proc ; loops back to _procs, second row

REP instructions work like LOOP instructions, but are specifically customized to handle strings (this is where IA-32 assembly almost becomes a high level language)

mov esi, str1

mov edi, str2

mov, ecx, 10h

rep cmps

What happens here is that the strings to be compared are loaded into ESI and EDI and then a comparison is performed for 16 bytes (hexadecimal value 0x10 = 16 in decimal notation). If at some point the source and destination are not equal, a flag will be set and the operation will be aborted.