Introduction

The Epicurean Paradox, a profound philosophical conundrum, has intrigued thinkers for centuries. Named after the ancient Greek philosopher Epicurus, it presents a compelling challenge to the traditional concept of an omnipotent, omniscient, and omnibenevolent God. The paradox grapples with the existence of evil in a world supposedly governed by a benevolent deity, raising questions that have become central to theological and philosophical debates. This paradox, while rooted in Western philosophy, finds intriguing responses in the philosophical traditions of the East, particularly in the Advaita Vedanta school of Hindu philosophy. This blog post aims to explore the Epicurean Paradox in detail and delve into how Advaita Vedanta provides a unique perspective to resolve this paradox. Through this exploration, we will journey into the heart of one of philosophy’s most enduring questions and discover how ancient wisdom can offer insights into modern dilemmas.

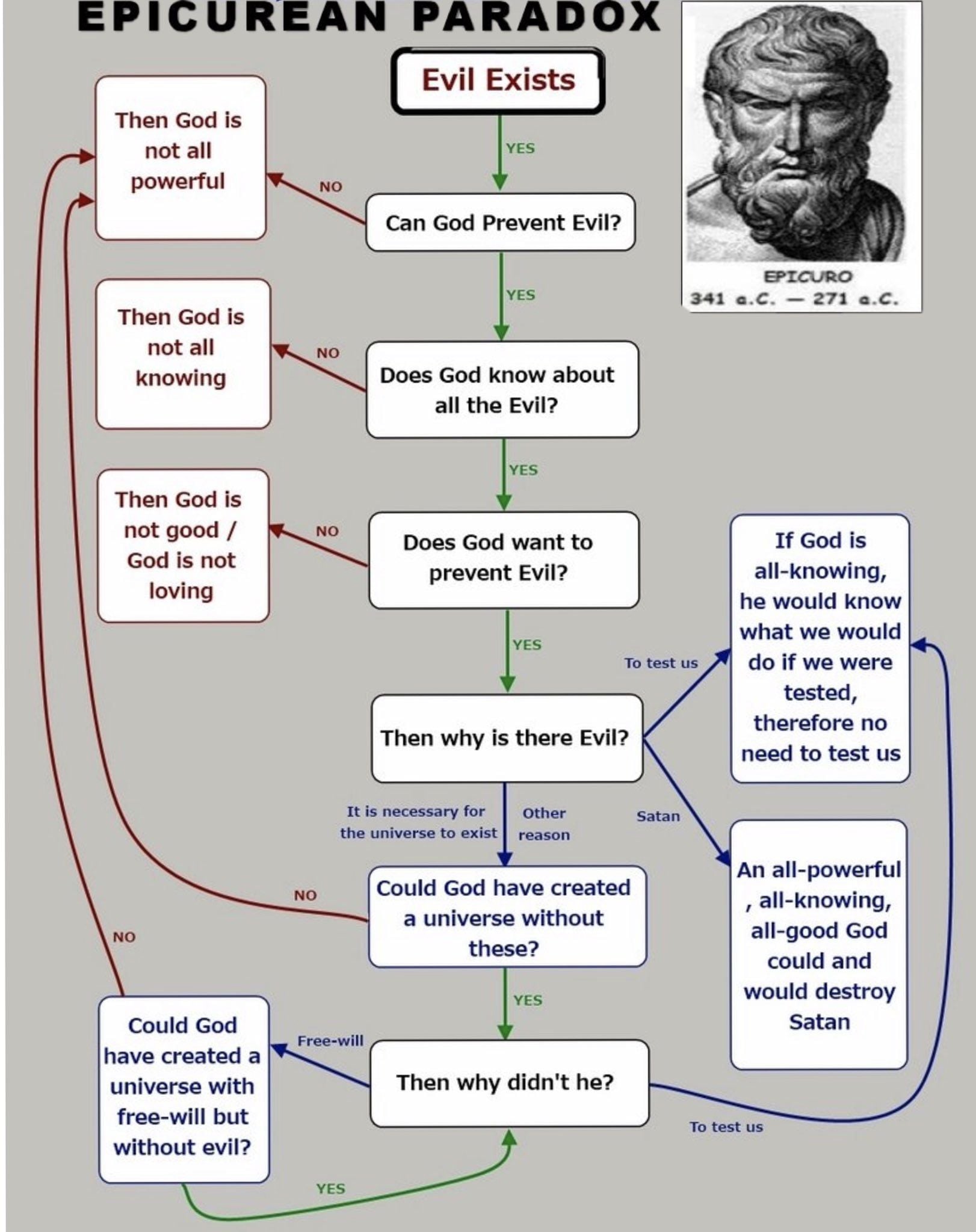

Understanding the Epicurean Paradox

The Epicurean Paradox is a powerful argument against the existence of an all-knowing, all-powerful, and all-good God. It is articulated as follows: If God is willing to prevent evil, but not able, then he is not omnipotent. If he is able, but not willing, then he is malevolent. If he is both able and willing, then whence cometh evil? If he is neither able nor willing, then why call him God?

This paradox raises a significant challenge to theistic belief systems, particularly those that posit a God who is simultaneously omnipotent, omniscient, and omnibenevolent. The existence of evil and suffering in the world seems incompatible with such a God. If God is all-powerful, he should be able to prevent evil. If he is all-knowing, he would be aware of all evil. And if he is all-good, he would want to prevent all evil. Yet, evil persists, leading to the question: how can such a God exist?

The Epicurean Paradox has been a central point of contention in theodicy, the branch of philosophy that tries to reconcile the existence of an all-good, all-powerful God with the presence of evil and suffering in the world. Various responses have been proposed, ranging from the free will defense to the notion of evil as a necessary counterpart to good. However, these solutions often raise further questions, leaving the paradox largely unresolved in many philosophical traditions.

Advaita Vedanta: An Overview

Advaita Vedanta, one of the oldest and most influential schools of Hindu philosophy, offers a unique perspective on reality and the nature of the divine. The term ‘Advaita’ translates to ‘not-two’, signifying its fundamental premise of non-dualism. According to Advaita Vedanta, the ultimate reality is Brahman, an infinite, formless, and eternal entity that transcends all concepts and categories.

The world as we perceive it, with all its diversity and dichotomies including good and evil, is a result of Maya, often translated as illusion or ignorance. Maya makes us perceive the one, undifferentiated Brahman as the diverse world. It is akin to mistaking a rope for a snake in dim light. The snake doesn’t exist, but due to the illusion, we perceive it as real.

At the individual level, Advaita Vedanta posits that the self (Atman) is identical to Brahman. The perceived separation between the individual self and the ultimate reality is again a result of Maya. This ignorance (Avidya) of our true nature is the root cause of all suffering.

The goal of life, according to Advaita Vedanta, is to realize this fundamental truth, to see beyond the illusion of Maya, and to recognize our true nature as Brahman. This realization leads to liberation (Moksha) from the cycle of birth and death, and the dichotomies of good and evil.

The Advaita Vedanta Perspective on God and Evil

In the framework of Advaita Vedanta, the concept of God is synonymous with Brahman, the ultimate reality. Brahman is beyond all dualities, including good and evil. It is formless, infinite, and eternal. The world as we perceive it, with all its dichotomies, is a result of Maya, the cosmic illusion.

Evil, in this context, doesn’t exist independently but is a result of ignorance or Avidya. It’s a misunderstanding of our true nature as Brahman. When we perceive ourselves as separate entities, we act out of self-interest, leading to actions that can be classified as ‘evil’. However, these actions are not evil in themselves but are seen as such due to our limited perspective.

The existence of evil, then, is not a reflection of the nature of God (Brahman) but a result of our ignorance of our true nature. It’s a part of the illusion created by Maya. This perspective reframes the problem of evil. It’s not a question of why an all-powerful, all-knowing, and all-good God allows evil, but rather a question of why we, in our ignorance, perceive and commit evil.

The solution to the problem of evil, then, is the realization of one’s true nature as Brahman. This realization, termed as Moksha or liberation, leads to the dissolution of all dualities, including good and evil. It’s a state of ultimate peace and bliss, beyond all suffering and evil.

Resolving the Epicurean Paradox through Advaita Vedanta

The Epicurean Paradox, while challenging theistic belief systems that posit an omnipotent, omniscient, and omnibenevolent God, finds a unique resolution in the non-dualistic philosophy of Advaita Vedanta. The paradox hinges on the existence of evil in a world governed by a benevolent deity. However, Advaita Vedanta reframes this issue by positing that the ultimate reality, Brahman, is beyond all dualities, including good and evil.

In Advaita Vedanta, evil is not an independent entity but a result of ignorance or Avidya. It arises from the illusion of separateness, which leads to actions driven by self-interest and perceived as evil. The existence of evil, therefore, is not a reflection of the nature of God (Brahman) but a result of our ignorance of our true nature.

The resolution of the Epicurean Paradox, then, lies in the realization of one’s true nature as Brahman. This realization, termed as Moksha or liberation, leads to the dissolution of all dualities, including good and evil. It’s a state of ultimate peace and bliss, beyond all suffering and evil.

Through this lens, the Epicurean Paradox is not a refutation of God’s existence but a call to understand the nature of reality beyond the illusion of Maya. It’s a call to awaken to our true nature as Brahman, transcending the perceived dichotomies of good and evil.

Conclusion

The Epicurean Paradox, a compelling argument against the existence of an all-knowing, all-powerful, and all-good God, has been a central point of contention in philosophical and theological debates. However, the non-dualistic philosophy of Advaita Vedanta offers a unique perspective that reframes the paradox and provides a resolution.

In Advaita Vedanta, the ultimate reality is Brahman, which is beyond all dualities, including good and evil. The existence of evil is seen as a result of ignorance or Avidya, a misunderstanding of our true nature as Brahman. The solution to the problem of evil, then, is not the intervention of an external deity, but the realization of our true nature. This realization, termed as Moksha or liberation, leads to the dissolution of all dualities, including good and evil.

Through this exploration of the Epicurean Paradox and its resolution in Advaita Vedanta, we see how ancient wisdom can shed light on modern philosophical dilemmas. It invites us to look beyond the apparent contradictions and dichotomies of the world and to recognize the underlying unity of all existence. It’s a call to awaken to our true nature and to transcend the perceived boundaries of good and evil.